I’ve been working as part of a central team in a multi-academy trust in Somerset for the best part of two years now. Whilst I recognise my ignorance is still far-reaching, I’ve also – through my own work and visits to/conversations with colleagues in other trusts – started to form an understanding of how trusts can work to improve schools. That’s what I’m thinking about when I write talk about these metaphors below but they could apply to any leader at any level thinking about improvement in a single school, department or classroom.

1. A Mirror

What it is: Presenting reality in classrooms to teachers and leaders as accurately as possible.

Works well for:

- Supporting an individual teacher with their development goals

- Sharing a picture of T+L in a department, phase or school

- Assessing the implementation of a new strategy or policy

Some activity holds a mirror to reality, making it visible to those who need to see it. This is particularly useful when there has been a plan, an intention or a goal. Our understanding of the desired state is held up against the reality as we find it.

Perhaps this seems unhelpful or basic. You’re just pointing out what is or isn’t happening. It doesn’t necessarily require expertise to do this; the main thing you need is time. But the mirror, whether you are a middle or senior leader or work for a central team, respects the individual or team you’re trying to help improve.

They’ve said X should be happening. You listen and try to understand what X is, how it will operate and adapt in different classrooms. This might be the feedback approach in a particular department, an individual teacher’s implementation of mini-whiteboards or a school’s current T+L priority.

Working in this way prompts some questions.

How do you present ‘reality’ to a teacher or leader?

Here, we need to listen very carefully to the intentions of those we’re working with.

You’ve said every lesson should have mini-whiteboards/cold call/visualiser use/the same booklet/this structure to writing paragraphs/this call to attention… How would we expect that to vary from teacher to teacher? What should everyone do?

Once we’ve got that information, we can go into lessons ready to seek it out and present a factual account of how it is happening:

You said the majority of lessons should include MWB checks for understanding. We saw this in 7/10 lessons.

You said every paragraph should follow the same structure. Every lesson observed included the structure but teachers had adapted it in following ways… Is this ok?

How can you be a helpful source of knowledge rather than an unfiltered stream of everything that is going right and wrong?

It isn’t helpful to share an unfiltered and unending stream of everything you’ve seen and heard. This work should be focused on what you, teachers and leaders have decided needs attention and, crucially, when it needs attention.

Some of this work might fit into a kind of calendar or cycle. Our trust has days focused on doing this at the start and middle of the year. Some of this work might happen at appropriate moments in the school year. After a new approach has been trailed for half a term, for example.

How and when do you push back on the intentions given?

Acting as a mirror might suggest there is little opportunity to push back on or disagree with the intentions you’re assessing. But we can only disagree well with things we really understand. At times, it doesn’t take much knowledge to understand where you disagree; at others, we really need to dig into an idea, plan or practice. Having a common language or set of principles (for T+L, CPD, raising achievement, how we work) can be helpful to refer back to so that disagreement is not just between individuals but against an agreed upon set of ideas.

2. A Spotlight

What it is: Sharing practice that is helpful to the teacher, team, leader or school and that can be accessed, visited, seen, collaborated on.

Works well for:

- Helping colleagues to collaborate

- Clarifying next steps for teachers and leaders

- Finding solutions to problems identified

Being able to see teaching and leadership across a school or group of schools is a privileged position. Very few have this vantage point and it shouldn’t be taken lightly.

Unlike the mirror, you need to cultivate your ability to be a spotlight by knowing teachers, classrooms, teams and schools really very well. I don’t keep a record of which teachers or teams are particularly good at different things but I’ve worked with teachers across our trust

A spotlight can be a bit of a blunt instrument if it tries to practices or strategies regardless of the need in front of us. So, instead of just regularly blurting out that one teacher should go to see another, you can structure use of the spotlight by:

a. Keeping track of what individual teachers are working on then connecting teachers to support development. In my trust we do this through the professional growth plans teachers write at the start of each year. Collating these we know what each individual is working on and then can pair up, make suggestions and enable collaboration or support.

I was walking down a corridor in one of our schools and a teacher asked me, ‘Who’s good at wait time when they’re cold calling?’ He’s been working on it but doesn’t feel he’s making progress. My mind went blank for a moment; I couldn’t think of anyone but I sifted back through memory and notes to find an answer. I try to be a presence in schools I’m in – on duty/on the corridors – because this is where these impromptu conversations might happen.

We can also engineer the sharing of ideas, problems and solutions by calendaring CPD that caters for specific needs we’ve identified. This works for individual teachers (for example, a group introducing mini-whiteboards for the first time are supported by someone with more experience of them). But it also works for middle leaders, connecting them with each other when you know there’s a lot of practice and resource that can be shared.

b. Recognising individual teachers. The reverse of the above is making sure that teachers feel comfortable with you going to them and saying, ‘Do you mind if I suggest Ben comes to see you model with the visualiser?’ The emphasis here is on the amazing things happening in the classroom and the desire for others to benefit from them. To do this we also video lessons and have a central hub where staff can watch them.

c. Identify specific solutions to well-defined problems. It’s easy, particularly as a non-specialist, when you’re talking to a subject specialist to try to shoehorn in your narrow experience of the subject. So a history teacher is telling you about the difficulties they’re having and you don’t listen very well but jump in with the great history teaching you’ve seen recently. It’s harder to listen, question and understand to the point where you have something useful to say. The same as true with whole school strategies. School X have just introduced a school-wide metacognition strategy; it looks like it’s going well. We should do it here. We can rush our way through this thought process before we’ve really decided what problem it would solve.

Of course, structures that help teachers make the most of that spotlight. We’ll turn to those next.

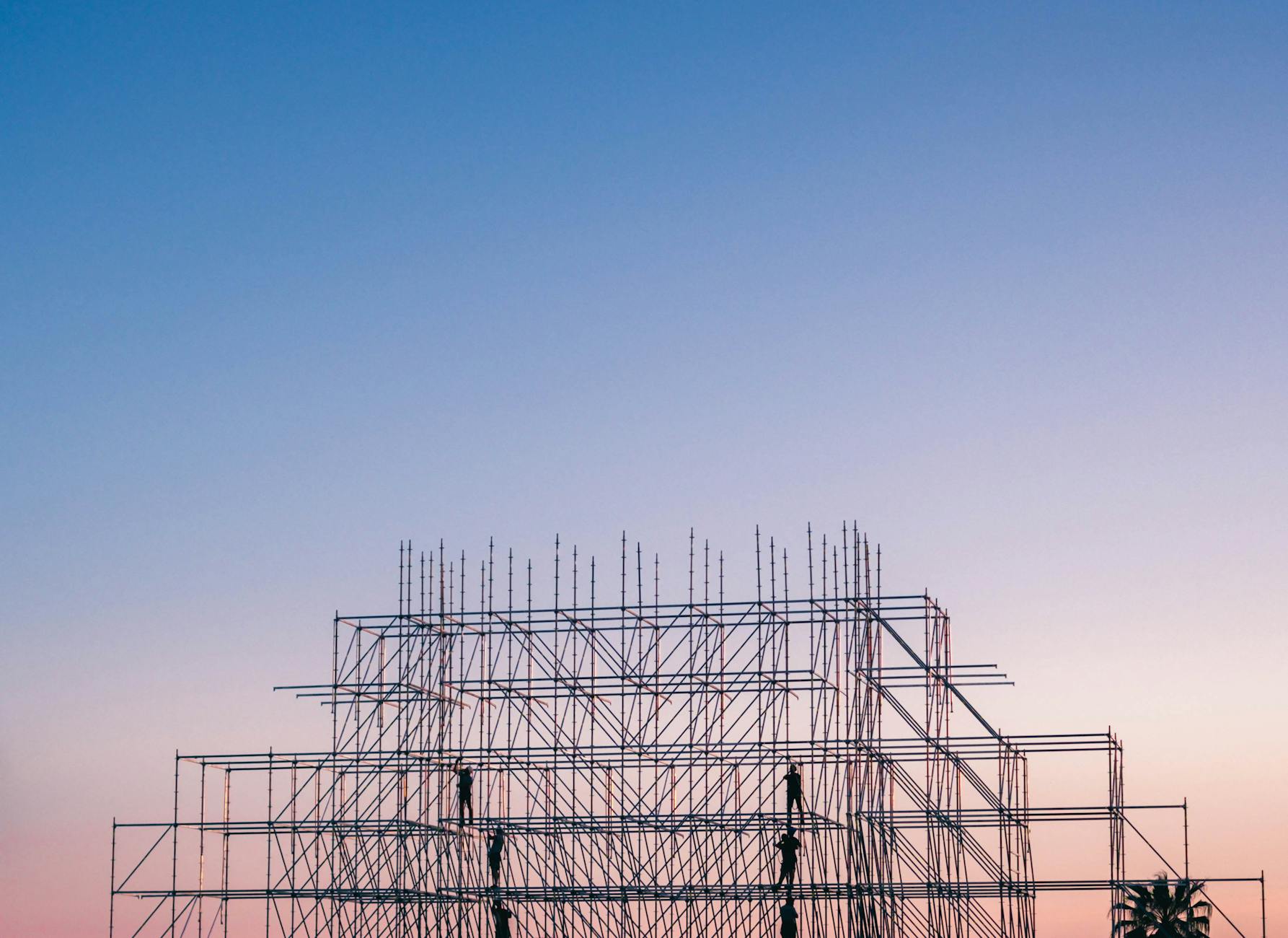

3. A Scaffold

What it is: The structures a trust embeds that determine the type of staff development/school improvement work that happens.

Works well for:

- CPD programmes

- Systematic collaboration

The scaffold is generally what is expected of trusts: set out the policies and procedures that everyone will have to follow. In the worst cases, rigidity makes the scaffold more of a straitjacket but it doesn’t have to be like that.

There’s two ways I’ve experienced this working well.

1. A common approach to teacher development

In our trust, each school uses the Growing Great Teachers programme developed by Chris Moyse. Each teacher has a goal they are working on, a broader area of teaching they are trying to improve. Teachers regularly check-in on this with colleagues, talking through their progress. They also regularly receive feedback through drop-ins to their lessons.

The above is what every school does but schools add to this in other ways. They might share progress in briefings, decide on common areas to work on, plan additional CPD that supports the goals of their teachers.

The scaffold is the process but the way it is used is specific to the school. In larger primaries and secondary schools the phase or subject team is the main vehicle of the Growing Great Teachers process. In smaller primaries, this wouldn’t work.

It also works best where teacher choice is balanced carefully with the needs of the school. If a school is working on increasing participation, leaders might encourage more talk partners and mini-whiteboards in the goals of teachers.

2. Subject collaboration

In our trust, we have subject leads who teach four days a week and one day devoted subject work. These leads:

- Regularly visit schools to support teachers, leaders and the development of the curriculum.

- Run development days (training/collaboration days) for heads of department.

- Have online meetings to discuss specific aspects of the curriculum, staff development or problems we’re working on.

- Run our online Teams where resources are shared and questions asked. This is where, at their best, networks really form.

The scaffold is the specific activity – school visits, development days, online meetings – but the work varies to meet the need of the school.

One thought on “Metaphors for School Improvement Work”